Apple and Epic games (the makers of Fortnite) have been going at each other for almost a year now. And finally a ruling from a Federal judge might just settle the matter. But with one caveat - "It might have broad implications for Epic Games, Apple and Big Tech as a whole."

The Story

Before we get to the ruling, some context —

Epic is a video game developer. They also make cool software. Think Unreal Engine — a platform where other creators can make their own video games and build something even cooler. Led by Tim Sweeney, the company has always been a poster child within the gaming community. However, they’ve catapulted into mainstream media largely thanks to the popular battle royale game Fortnite. If you haven’t heard of Fortnite we urge you to find a 20-year-old and ask them to give you a quick rundown. I promise they’ll do better than us.

In any case, Fortnite is a money minting machine. In 2019, Fortnite brought in revenues of $1.8 billion. Players can buy costumes, virtual dance moves, and pre-released game modes inside the app using special in-game currency called V-Bucks. You can earn free V-Bucks by playing the game or you could choose to buy them instantly by paying actual money. And if you’re on a mobile phone using Android or iOS, all in-game purchases are routed through the App stores. Meaning Apple can collect close to 30% on all payments made to Epic Games and Fortnite without actually adding much value.

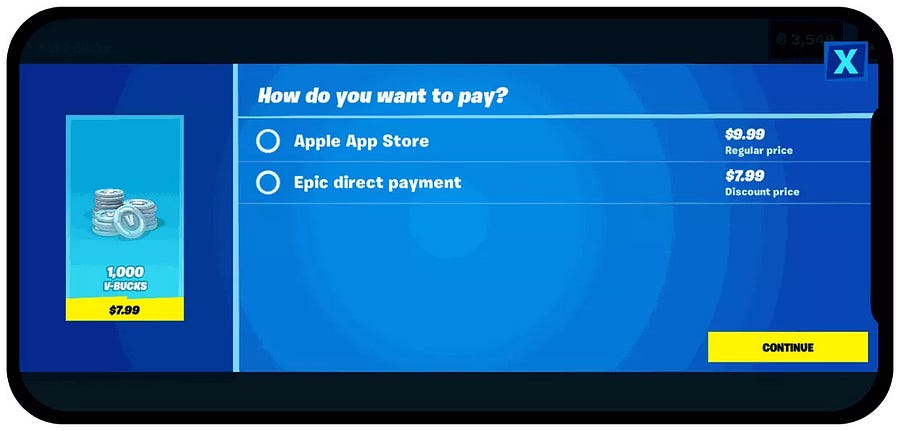

Epic complied with these rules (for the most part) until August 13th 2020, when they offered users an alternate payment option within the game by offering a discount.

And then…

All hell broke loose. Apple kicked Fortnite off the App Store for violating its guidelines and released a statement lamenting Epic Games’ decision. Epic, in turn, filed a lawsuit seeking a court order to dismantle Apple’s commission structure and offer users the choice to install software on iPhones outside the confines of the App Store.

And they’ve been duking it out ever since.

The only problem — Despite a federal judge ruling on the matter, there doesn’t seem to be a clear winner.

Epic Games’ main contention was this — “Apple, through its control of App store wields a monopoly. If you’re a game developer and you want to market your products and services on Apple devices, you have to route all your transactions through Apple’s App Store — the infamous walled garden. This effectively means consumers have no choice and they’re tied into this equation perpetually. So if this isn’t a classic case of a monopolistic enterprise, what is, eh?”

But this line of reasoning isn’t very solid. Apple can contest that this is a moot argument for all practical purposes. You can’t define a single market this way. Apple holds a fraction of the market share in the smartphone segment. They don’t control the mobile OS segment. They don’t have a dominating market share in mobile gaming or the apps segment. The only argument Epic has on its side is that Apple has complete dominance in the “apps for iPhones segment.”

But how can anybody in good conscience define a market this way? Isn’t this cherry-picking at best?

Well, not entirely.

There is this idea of a foremarket and an aftermarket. Think of it this way—When you buy a printer, for instance, you may have the option to choose from a broad range of manufacturers. This is the fore market, where competition is rife. But once you pick a manufacturer, you have to buy toners from this company and this company alone. And that means the aftermarket for your printer is dominated by just one player — the manufacturer. In fact, in some cases, companies subsidize the cost of the printer to make money in the aftermarket selling ink. It’s common practice in many industries.

And back in the 1990s when Kodak began engaging in a similar enterprise, the Supreme Court castigated them from dabbling in what they believed was an anti-competitive program. Kodak held a 2% share in the photocopier segment. However, at one point they refused to sell spare parts to third-party companies offering after-sales photocopier services, thus effectively monopolizing an important aftermarket. Kodak argued that customers had a choice to pick any photocopier they liked. But considering customers couldn’t service their photocopiers outside Kodak’s ecosystem, the Supreme court still held that the company was engaging in anti-competitive practices, by not selling parts to third-party services.

So technically you could argue , that although Apple doesn’t have a dominant market share in the smartphone segment, they have a near-monopoly in the “Aftermarket” — where they sell apps for iPhones. But once again, the judge didn’t see it this way. She believed the relevant market, in this case, was “mobile gaming transactions” and Apple did not hold a dominant market share in this segment. There's Android, Microsoft and a whole host of other platforms that facilitate mobile gaming. So the judge ruled that Apple did not violate anti-competition laws.

But, Epic did get something out of this. The judge also ruled that Apple had to offer developers the room to introduce their own payment portals. That Apple cannot stop companies like Epic from providing buttons or links in their apps that direct customers to pay outside of Apple’s own in-app purchase system. So by all accounts it seems, the company can offer customers the option to bypass the 30% commission or the so-called “Apple Tax.” But unfortunately, they couldn’t get the judge to allow customers the right to download apps outside of the App Store.

So yeah, both parties got something out of this. But it doesn't seem as if they're happy with the state of things. It's likely that both parties will appeal the ruling and we may see a part-3 brewing very soon.

Until then...

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp, LinkedIn and Twitter