The hottest IPO of the year is all set to hit Dalal Street this week and if you're looking for a simple article to walk you through the entire issue, this is the story for you.

The Story

It’s happening. The Zomato IPO will finally be here this week. And you can possibly get your hands on one of the hottest internet startups of our generation.

And boy oh boy is it hot?

In the last few years, Zomato has gone from being a promising young startup to a burgeoning behemoth. From processing a mere 30 million orders in 2018 to processing close to 400 million orders in 2020. From making just ~1,400 crores in 2019 to earning upwards of ~2,700 crores the very next year. From partnering with just a few thousand restaurants to close to 4 lakh partner restaurants, Zomato has in fact come a long way.

But perhaps their biggest achievement so far has to be the improvements they’ve made in the unit economics department.

What’s that you ask?

Well, let’s take it from the top.

Each time you place an order, you pay a certain sum to Zomato (less of all discounts). Zomato takes a cut here and they promptly transfer what’s left to restaurants. This is an oversimplification, but hopefully, it should get the point across i.e. If Zomato can ferry an order by spending ₹10 and make ₹11 via commissions and delivery charges, then it has positive unit economics. Each order is contributing to the bottom line, in a nice way. Unfortunately, for the longest time, Zomato simply didn’t have this bit sorted. They couldn’t make break-even here.

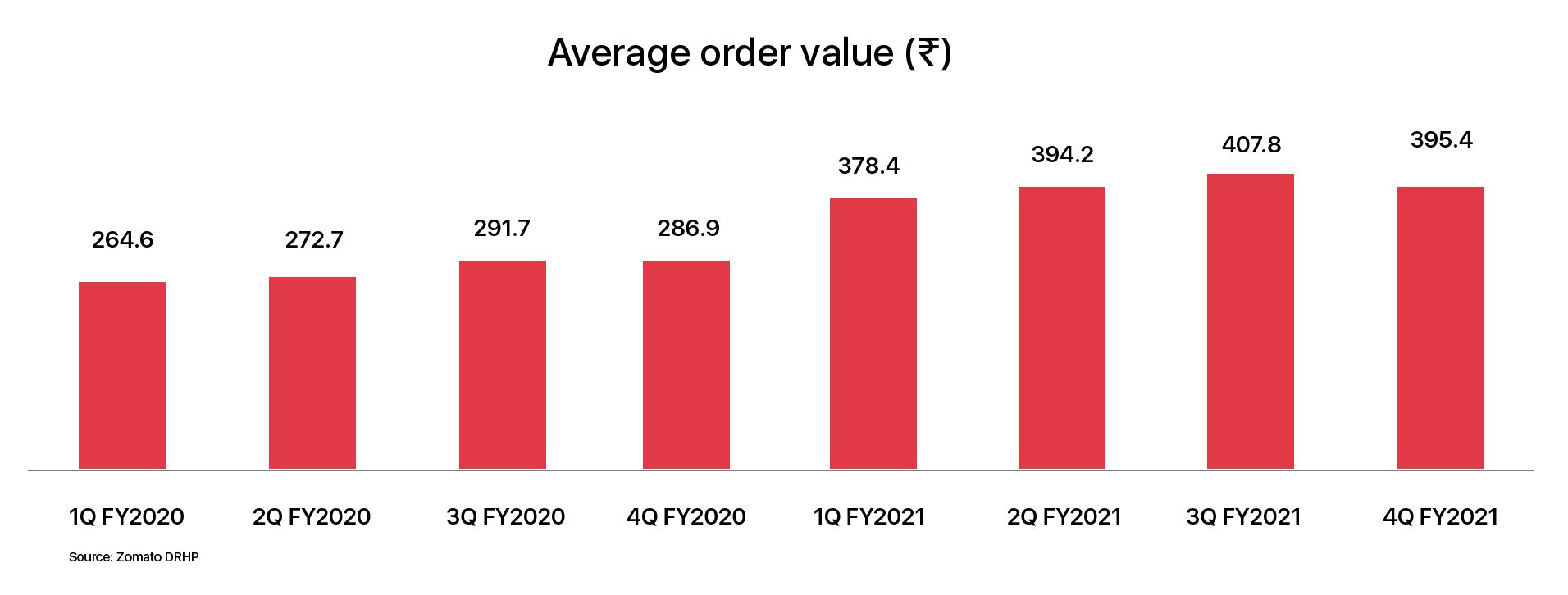

However, that changed during the pandemic. And to see how that happened, you may have to look at a metric called the average order value (AOV).

The average order value as the name indicates is the average value of any order placed on the app. So if you have 3 orders with values ₹200, ₹300, and ₹400. The average order value, in this case, is ₹300. But here’s the catch — If the average order value keeps climbing, then Zomato has a better chance of breaking even and perhaps turning a profit on each order.

The logic here is simple — Zomato spends pretty much the same kind of money ferrying a ₹100 order and a ₹500 order i.e. the costs more or less remain the same. But they make more money from the ₹500 order, by virtue of claiming a commission on the total order value. A 20% commission on ₹100 tallies up to ₹20. On an order value of ₹500, the commission jumps to ₹100. The second transaction is a more profitable enterprise and if customers routinely seek more expensive orders, then you will witness an uptick in average order value. The increase in average order value in turn will help Zomato improve the unit economics. This is the path to profitability and during the course of the pandemic, that is precisely what transpired.

The average order value rose — from ₹264 for the period between March and June 2019, to about ₹400 during the last 3 months of 2020. That means the average customer on Zomato is now spending more money than he/she used to.

Why is that happening you ask?

Well, there are many reasons. One possible thesis is that there has been a distinct change in listing patterns. We saw premium restaurants pivot to deliveries and takeaways for the first time ever. As people refused to frequent restaurants, these high-end restaurants had no choice but to list their offerings on apps like Zomato. And as such, people now had the luxury to order high-value items from these outlets, and price patterns across the app witnessed a shift.

Outside of this, there was also a change in Zomato’s customer demographic. You know who’s likely to order from Zomato — It’s the lone bachelor living in an urban center with little incentive to cook. These were the original loyalists — people like myself. However, as Covid induced lockdowns became commonplace, the bachelors migrated home and a very different set of consumers started exerting their influence — families. As Zomato noted in an interview back in September 2020 — “Orders with meals for 3 or more persons have recovered well and are higher than even pre-covid levels currently”

But are they really families?

Well, there’s also the hypothesis that this may have been a function of the lockdown. If you’re all huddled indoors, it’s likely a single individual will take the mantle and order for multiple people at the same time. It’s perhaps one of the reasons why average order value shot up so drastically. But it’s also one of the reasons why many people think this is unsustainable.

Because at the turn of 2021, people were already adjusting to the new normal. And while the company still boasted positive unit economics, the average order value had declined — possibly indicating that it may be harder for you to make a sizeable profit on each order while also trying to court new business.

Also, despite the positive commentary surrounding the company, the lockdown hasn’t been very kind to Zomato.

Revenues took a beating. There was a visible dip in gross order value (GOV) during the first few months. There were fewer active users on the platform and even fewer transacting users. More importantly, the company is still loss-making. Yes, they are turning a profit on each order, but this doesn’t include fixed costs like advertising and marketing expenses. So despite the fact that Zomato now boasts positive unit economics, the other numbers don’t really inspire a lot of confidence.

But what about the other lines of business? Shouldn’t that count for something?

Well, of course, it does. We know they still make a little bit of advertising revenue. We know they make some money by helping restaurants with procurement. They also recently invested in Grofers, and will possibly start dabbling with online groceries soon enough. But right now, the only thing that dominates the top line is the food delivery business. And that’s how people will value the company.

Which finally brings us to the valuation conundrum. In the prospectus, Zomato casually notes that they have no listed peers in India. That you can’t compare them with anyone because they stand alone at the precipice of a new era. It’s like this — “If Swiggy had gone public before Zomato, then Swiggy would have been a listed peer. We could have compared their sales figures and scrutinized what people were willing to pay for these shares. But since that hasn’t happened yet, the only way to compare is to look at global peers.”

Some people think looking at Doordash is a good option. It’s a US food delivery company that only recently went public with an eye-popping valuation. But here’s the thing — “These two companies are still miles apart.”

Doordash has better growth numbers. They boast higher order values. They make more revenues and operate in a more mature market. And their shares still aren’t as expensive as Zomato’s. Does it mean Zomato is overvalued then?

Well, not so fast.

Zomato will argue that they have so many things going for them. The food services industry still only contributes only about 8–9% to the food market in India. Compared to countries like the US and China this is a pretty nominal figure. In these countries, they make up nearly 40%-50% of the food market. So there's clearly a lot of room for growth.

The sceptics will turn and argue that this only complicates matters further. Zomato has the unenviable task of breaking new ground and growing at an exorbitant pace, while also simultaneously improving margins. And doing so when you have companies like Amazon snipping at your heels, may not be that easy.

So we have conflicting theories. Some will argue that the company is ridiculously expensive. Even others will tell you that the premium is warranted. Some will tell you that positive unit economics should breed optimism. Even others will tell you that the contribution will dissipate as they continue to fight for market share.

Ultimately, you’ll have to make up your own narrative. Do you think Zomato can defy all odds and justify its lofty valuation? Or do you think the optimism is unwarranted?

Let us know your thoughts on Twitter.

Until then…

Don't forget to share this article on WhatsApp or Twitter.

Note: The company is looking to raise 9000 crores to fund organic and inorganic growth over the next few years. Infoedge, one of the investors is also looking to sell its stake worth 375 crores.